In Japan, it is a well-known fact that if a person loses an item or forgets something on public transportation, the chances are very high that it will be returned to its rightful owner.

Japanese people, in general, view the basic act of returning lost articles to be a communal responsibility, so children are taught from an early age to respect other people’s property, and if something doesn’t belong to you, don’t take it, and try to find its owner. This custom fosters the idea that everyone must be proactive in maintaining an honest and trustworthy environment in society.

One Japanese custom I find heartwarming is how if a person does drop a glove while rushing to a train or bus, or forgets an umbrella somewhere, or inadvertently drops a bicycle key while rushing to another location, the person who finds it will pick it up and place it in a conspicuously easy place to spot, usually up high, so the person who lost it, often retracing their steps, will notice it.

I have seen so many different types of objects placed higher than ground-level by people hoping that the rightful owner will backtrack his or her steps and find them.

Japan even has a “Lost Goods Law” that requires anyone who finds a lost item to return it as quickly as possible to its owner or to a police box in case the person who lost it goes to the police to report the lost item. If the item is then returned to its rightful owner, it is proper etiquette for the owner to reward the person who found it with at least 5% of its value, but usually no more than 20% of its original value (which is considered appropriate).

Over 30 years ago, as I was leaving the train station in the city where I lived, I found a man’s wallet on the ground. The police box was next to the station, so I walked it over to the police box and handed it over. I had to give my name and contact information to the police. It turns out that it was a college student’s wallet that he had dropped accidently while rushing to catch a train after buying his ticket; he was very happy to get his wallet back when the police called him to tell him it had been found and turned in.

The police called to ask if I wanted a reward, and I said it wasn’t necessary, and I was merely glad it got returned to its owner. Later, the boy called to thank me for finding it and turning it in. I was just happy that, as a foreigner, it showed that we can be honest, too. So often, there are stereotypes here that put foreigners in a bad light, and it isn’t just by the general citizenry. Sometimes actual city offices and police departments are guilty of racial profiling that suggest that people need to beware of foreigners and to look suspiciously at us or to preemptively suspect us of doing something unlawful.

Foreigners are sometimes stopped by the police as “random checks,” which can be very annoying if you are just walking or riding a bicycle. I have heard many stories of foreigners riding bikes being stopped because the police suspected that the bike had been stolen. Again, are Japanese people stopped as often to check if the bicycle they are riding is stolen? With white-collar crime so high in Japan with embezzling and bribing, the police might spend their time more productively investigating these crimes rather than the random foreigner going about their daily lives on a bicycle.

I have even seen PSA posters that depict foreigners as thieves and miscreants to warn people of potential crimes and other misdeeds. These always portray the bad guys as nefarious and shifty-looking characters, and more times than not, they look more foreign than Japanese.

Just to be clear, there are crimes committed by Japanese on Japanese, so foreign crime, while definitely not zero, does not warrant the pearl clutching that tends to happen with regularity here. In fact, it is actually very small when comparing it to the overall percentage of crimes committed in Japan.

I read a statistic that only 5% of all arrests for criminal offenses in Japan are perpetrated by foreigners or non-Japanese. The percentage of Japanese citizens arrested for a crime is around 0.15% to 0.2% of Japanese citizens. So, overall, very low in comparison to other industrialized countries. It is just frustrating sometimes that anytime anything happens, it is the foreigner who is suspected first, which doesn’t seem fair.

But the cultural concept of making sure lost items get back to their rightful owners is a tradition and custom of Japanese culture that is endearing and nice. A colleague recently told me he had gone to McDonald’s for lunch and soon realized he had left his favorite hat on the seat. When he arrived back to check, it wasn’t there, but when he asked at the counter, someone had turned it in, and the McDonald’s staff had put it in a pristine bag and sealed it with the time and exact location where it was found written on it. This type of attention to detail is quite common here.

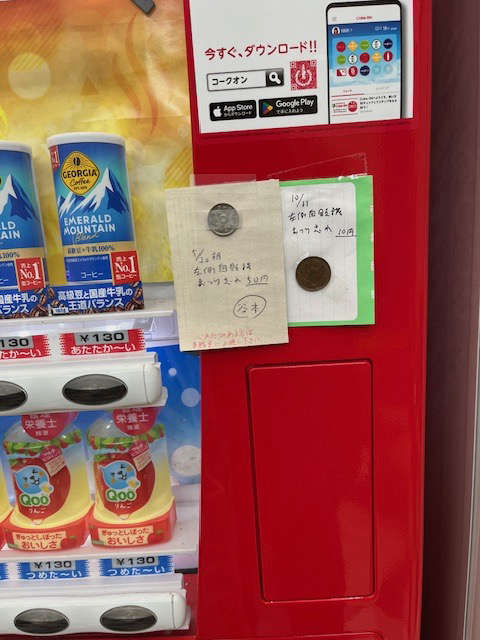

My original idea for this column is related to the attached photo. The vending machine in the foyer of the university building where my office is located has two notes attached to it with coins taped to them. The one note with the 50-yen coin states that somebody left the ¥50 in the change slot, and the name of the person who found it is “Tanimoto.” The note, dated May 20, happened to be placed over another note that has 10 yen taped to it with a similar message, but it is dated Oct. 11. This indicates to me that the October 11 coin that was placed there is from well over a year prior, as the May 20 note and coin was placed on top of the other one.

The people who found these coins went to the trouble to get tape, paper, and a pen to leave the coins and messages, hoping the person who left the change would find it and retrieve it. I suspect that if someone in the U.S. found forgotten change in the coin slot of a vending machine, he or she would view it as a lucky chance-happening and exclaim “Finders keepers; losers weepers,” and claim it as his or her own, tucking it away in their pocket, smug and satisfied to have found a bit of money.