bob-knight-s-shelbyville-connections-reveal-a-kinder-side

Bob Knight will be remembered as one of the most significant figures in the history of basketball. His philosophy revolutionized the game. He played on a national championship team, recorded three NCAA championships as a coach and is a member of the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame, The National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame, The Indiana University Athletics Hall of Fame, and The Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame.

Knight’s profound influence extends to every aspect and level of basketball. He was the ultimate luminary to a generation of Hoosiers.

Tributes and commentary have poured in from every available level of communication and media following the former Indiana University coach’s passing on November 1. His volatile demeanor and occasional outlandish behavior came to define the man over the course of his career. One too many such incidents resulted in his dismissal as IU basketball coach in the fall of 2000 after 29 years of unprecedented success.

Knight’s humanitarian efforts such as extensive financial contributions to the university’s library, emotional support for players enduring life’s most difficult and challenging moments such as that provided in the cases of Mike Krzyzewski and Landon Turner, and numerous other little- known, remarkable acts of kindness received marginal attention.

The coach never publicized or promoted these philanthropic endeavors and as a result, the public persona of Knight as a self-serving, volatile, egomaniac came to be accepted as fact. However, this caricature provides only a snapshot in to the essence of the man.

The truth is that Bob Knight was a complicated, somewhat contradictory individual whose heartfelt mission on his journey to success was to contribute to the enhancement of the lives of others. Several of his encounters with the Shelbyville community make a compelling case for support.

Jeff Lowe was a two-year starting center for the Shelbyville High School basketball team. He led the Golden Bears in scoring his senior season and received the prestigious Paul Cross Award in 1971. Lowe enrolled at Indiana University and played on the freshman basketball team (freshmen were ineligible to play NCAA varsity sports until 1972). He was enthusiastic about having the opportunity to play at the college level and pursue his aspirations of becoming a teacher and coach.

Bob Knight was entering his second season as the IU coach and called Lowe into his office following preseason tryouts. Knight informed Lowe that he had been cut from the squad. The coach also told him that he appreciated his character and his effort. Knight concluded the meeting by telling Lowe, “If you ever need anything, let me know.”

Lowe became disheartened and lost interest in school. He left campus and came back to Shelbyville to work in a local factory. He had no intention of returning to Bloomington.

“I thought coach’s talk about me needing anything were just empty words and I did not want to bother someone as busy as he was,” Lowe said in a 1975 interview.

Knight heard about Lowe’s decision a month later and called the family’s home in Shelbyville. He asked Lowe’s parents, “Why wasn’t I informed of this problem earlier?” and arranged for Lowe and his parents to meet him at a basketball clinic he would be lecturing at in Indianapolis.

“He told us he wanted to quit when he was a player at Ohio State but was persuaded not to by his father,” said Lowe. “He stressed the importance of finishing school and what it would mean to my future.”

As Knight talked, Lowe noticed that Knight was already late for his lecture.

“He told me not to worry about that, that my future was what was important,” said Lowe.

The coach offered the Shelbyville graduate a job as team statistician and the opportunity to attend games and practices.

“He told me that he would teach me everything about coaching basketball,” said Lowe.

Knight continued and said that if he was not interested in the job as statistician, Knight would work to find him another school where he could continue his playing career.

Lowe (photo) accepted Knight’s offer, returned to school, and served as team statistician for four years.

“I’m learning something every day, I’m learning how to handle certain situations, I’m learning from the best,” Lowe further stated in 1975.

Jeff Lowe died in a car accident in 1980 at the age of 27. However, that tragedy is mitigated by the fact that he was treated to the experience of a lifetime by Bob Knight. He continued his education and made the most of the opportunity to indulge his love of basketball and pursue his passion. None of that would have happened were it not for Knight.

Steve Bush’s connection to Bob Knight is well-known. He was in the right place at the right time. Bush is a 1963 Morristown High School graduate and long-time Shelbyville resident.

He was working as a freelance photographer covering an IU game in late February of 1985 and captured the definitive, iconic photo of Knight throwing a chair from the team bench across the floor at Assembly Hall in the game against Purdue.

“I had a good spot very close to the IU bench,” said Bush. “Word quickly spread that I had taken THE picture and I was bombarded with requests for copies. However, given his reputation, I was a little nervous about coach Knight’s reaction.”

Bush’s concerns were completely unfounded.

“His secretary called me and said he wanted five copies,” said Bush. “He completely embraced the situation.”

Bush later received an autographed copy of the picture and a very nice letter from Knight.

“I was very surprised about how cordial and complimentary he was about everything. I was very grateful for his kindness and for him taking the time to do that for me,” said Bush, who still works as a freelance photographer.

Jeff Kolls was among a group of Indiana State Troopers who wrote Knight to inquire about purchasing tickets to an IU game. A miscommunication resulted in them missing the game that the coach had reserved for them.

“We called to apologize for the misunderstanding and coach Knight’s secretary called back and asked if we wanted tickets to the next game,” said Kolls. “After that, he provided the State Police Post with four tickets to basically every home game from 1996 through 2000.”

Kolls, a three-sport athlete at Shelbyville High School and 20-year Indiana State policeman who retired in 2000, went on to say that the tickets were premium seats.

“We always sat somewhere in the first three rows either behind the IU bench or directly across from it. We were so close behind the bench that you could hear the coaches talking strategy,” said Kolls. “You really felt a part of the game. We all truly appreciated coach Knight’s kindness. His secretary even took us back to his office to show us around during halftime of one game.”

Former SHS and University of Texas basketball standout Harry Larrabee (photo) reported several interactions with Knight. The coach sent one of his assistants to Shelbyville to meet with Larrabee during his senior season while coaching at Army.

“Coach Knight later called me,” said Larrabee. “No one knew who Bob Knight was in 1970, so he was just another voice on the phone to me.”

Larrabee went on to say that Knight told him that West Point was not for everybody and that he (Larrabee) needed to figure it out if he was interested.

“He was very clear and straightforward,” said Larrabee.

Knight and the Shelbyville native again crossed paths at the Far West Shootout in Portland, Oregon, in 1973 when Knight was at Indiana.

“We had just lost a tough game to West Virginia by one point,” recalled Larrabee. “As I was leaving the court, coach Knight approached me, put his arm around me and said, ‘Hey Shelbyville, hang in there. It’s a long season.’”

Larrabee appreciated that Knight took the time to console a fellow Hoosier at a tough moment.

Larrabee also spoke with Knight on occasions when Larrabee was men’s basketball coach and later athletic director at the University of Alaska-Anchorage in the 1990s. He said Knight praised the Alaska program for providing unique opportunities to players from remote areas. IU played in the 1995 Great Alaska Shootout that Larrabee coordinated.

Larrabee came to Bloomington to watch IU practice during one of his trips promoting the Shootout. He was invited to “the Cave,” the basketball inner sanctum beneath Assembly Hall afterward.

“The ‘cave’ experience is one I will always cherish,” said Larrabee about the two hours he spent discussing basketball and life with the legendary coach. He added that, “One of coach Knight’s most important goals was to empower student-athletes on and off the court.”

Knight’s passing has led Larrabee to positive reflection about his experiences with the late coach.

“Coach Knight had an authentic brilliance,” stated Larrabee. “I feel very fortunate to have had opportunities to interact with him throughout my career.”

These are just a few examples involving Shelbyville people that highlight the generosity and consideration the late IU coach demonstrated throughout his life. There are countless other similar instances.

Humans are complicated and Knight was no exception; paradoxical to be sure and undoubtedly more complex than most. He was, often to the extreme, both flawed and exceptional.

Yet, I believe history will confirm that throughout his life, he held and regularly manifested a genuine concern for others; a genuine though often camouflaged benevolence.

Bob Knight was more than simply the legendary coach who threw the chair. He had, at his core, a humanitarian spirit. That is how he should be remembered.

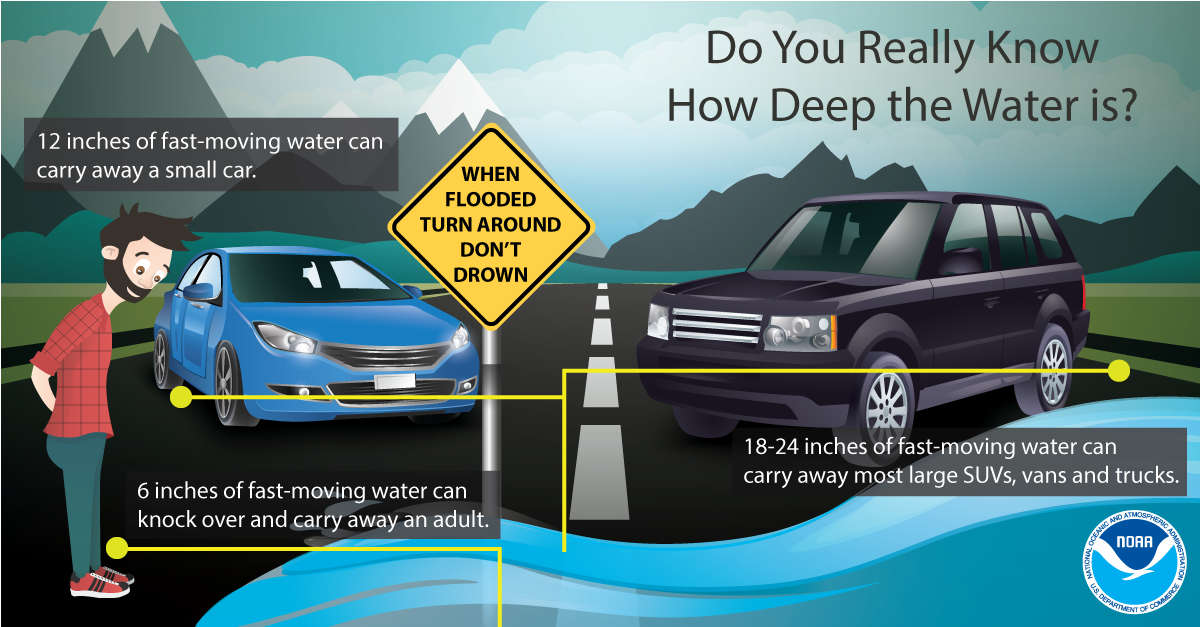

Flat Rock Christian Church offers shelter Wednesday with potential severe weather

Flat Rock Christian Church offers shelter Wednesday with potential severe weather

INDOT prepared for severe weather, widespread flooding through weekend

INDOT prepared for severe weather, widespread flooding through weekend

Legislation to provide FFA, 4-H students with excused school absences heads to governor

Legislation to provide FFA, 4-H students with excused school absences heads to governor

USPS calls for customers to help prevent letter carrier dog bites

USPS calls for customers to help prevent letter carrier dog bites

Henry Albrecht Memorial Fund Walk-A-Thon set for April 12

Henry Albrecht Memorial Fund Walk-A-Thon set for April 12

Shelbyville PD's Kyra Peoples among those honored for efforts to reduce drug-impaired driving

Shelbyville PD's Kyra Peoples among those honored for efforts to reduce drug-impaired driving

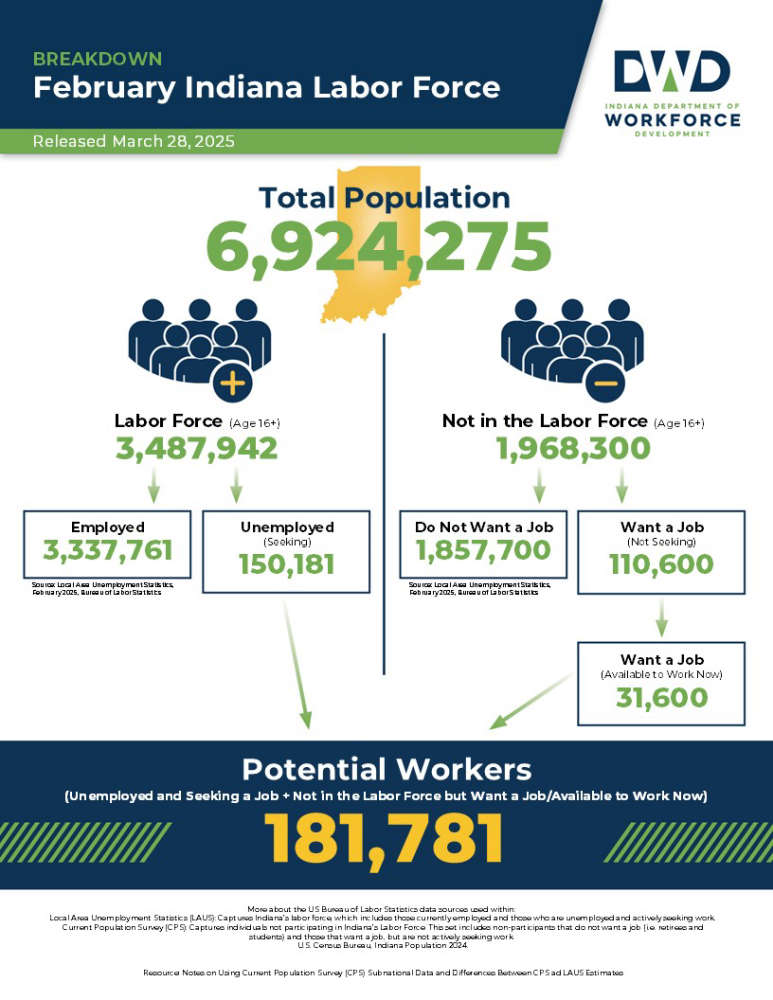

Indiana's total labor force hits new peak

Indiana's total labor force hits new peak