New Year’s Day (o shogatsu) in Japan is decidedly different than a New Year’s celebration in the United States. In Japan, it is very much a time for families to gather from near and far to come together as a family to share food, to pray together, and to say goodbye to the previous year while bringing in the new year.

Traditionally, Japanese people bring in the new year by making a visit to their local shrine either at midnight on New Year’s Eve, or on New Year’s Day, or within the first three days of the new year to pray and to wish for prosperity and good health for the upcoming year.

This visit is called “hatsumode” and it is basically the act of going to a temple or shrine for the first time in the new year during the period known as “sanganichi.”

Some shrines even feature festivals during the New Year (photo above).

One festival I have attended numerous times over the years is near where I live and men battle in fundoshi (traditional Japanese underwear) to covet a wooden ball (photo above). One team represents the mountain god and the other the ocean god and they try to wrestle it away from each other to get it into an opening at the shrine gate’s door. This is done while attendants constantly throw ice cold water on them along the long path to the shrine’s door, in January, which is quite cold!

A typical New Year’s Eve (omisoka — “misoka” means the last of the month and “O” means big) in Japan consists of the family members from far away arriving by early evening to begin celebrating together the holiday by eating “toshi-koshi” (year-crossing) buckwheat noodles. It is widely believed that eating buckwheat noodles on New Year’s Eve brings good luck, similar to the old American custom of cooking cabbage with a penny on New Year’s Day.

The idea of eating the buckwheat noodles is to let go of any negativity or hardships a person may have experienced during the previous year in order to welcome the new year with a renewed sense of starting anew.

This Japanese tradition of eating noodles on New Year’s Eve goes all the way back to the 13th century, and the reason noodles were originally chosen is that their long length symbolizes the wish for a long life and good health in the year ahead. Of course, according to Japanese eating etiquette, the noodles should be slurped up loudly while piping hot. It is in no way rude in Japan to make slurping noises when eating any type of noodles.

New Year’s Eve in Japan also features a variety of TV specials that Japanese people gather around the television to watch as a family. The most famous one, perhaps, is “Kohaku” (the Red/White Show) that features Japanese celebrities competing against each other on two teams — one team is red and the other team is white — in front of a panel of celebrity judges who decide the year’s winner.

In my 35 years of living in Japan, I have missed only a few Kohaku programs. The program ends just before midnight and then NHK has cameras set up at temples all across Japan and temple bells (bonsho) are struck right at midnight. This Buddhist event is called “Joya no Kane” (midnight bell). The bells are struck 108 times, marking the transition from the old year to the new year.

Why 108 times? According to Buddhist teachings, the number 108 represents the 108 possible worldly desires or passions that humans experience throughout their lifetimes. The idea behind this tradition is that by the time the last ring occurs in the new year that the person listening will not be bothered or burdened by their worldly passions and desires in the year ahead.

A sort of “spiritual cleansing”, so to speak, as a way to purge a person of the 108 earthly temptations that confront them as humans. These temptations are believed to be the source of people’s pain and suffering while on the earth plane.

Another custom in Japan at the end of the year is to do o-soji (big cleaning) where people and offices do a thorough and deep cleaning of everything so the New Year starts off crisp and fresh, similar to the U.S. custom of “spring cleaning.”

It is not uncommon to see sidewalks around companies and offices filled with inside furniture as the employees take everything out in order to clean every nook and cranny during this “big cleaning.” This cleaning includes scrubbing all the floors, walls, and ceilings, as well as all the crevices in windowsills, and basically every surface until everything sparkles and shines.

When employees return to work after the holiday, they come back to a pristinely clean work area to start their work anew for the new year. The original cleaning custom was called “susuharai” which mainly concentrated on cleaning the soot produced from burning a stove to stay warm and for cooking.

The practice started with the samurai but spread to commoners and is very closely related to Shintoism in the sense that it was a way to “purify” one’s surroundings, making it more pleasant for the “kami” (Shinto spirits and deities) to visit and linger around the space.

Shintoism holds purification rituals highly within its practices, so it makes sense that this would extend to people’s living and workspaces.

O soji also includes disposing of any clutter that may have accumulated over the previous year. It is a good time to get rid of any broken appliances, or unused items that tend to take up space and are no longer of any use to the household. It no doubt has a positive psychological effect on people, giving them a sense of accomplishment by offering them a way to mentally focus and condition their body, mind, and spirit by creating a clean slate, so to speak, for the year ahead.

One important caveat is needed here, though. If one doesn’t finish the cleaning chores and tasks before Jan. 1, it is important not to do them on Jan. 1, but to wait until at least Jan. 2, in order not to risk “sweeping away” any good luck that you are trying to attract into your home for the upcoming year.

On New Year’s Day, families gather around 3-5 stacked or tiered lacquered boxes called “jubako” to eat “o sechi ryori” which consist of traditional Japanese foods. These are prepared in advance, in order to give wives and mothers a break from cooking during the holidays in order for them to rest and enjoy themselves along with their families.

The custom of o sechi ryori began during ancient times, during the Heian Period (794-1185).

The traditional foods included in o sechi ryori all have very auspicious symbolism representing celebrations, fertility, longevity, and good luck. The point of eating o sechi ryori on New Year’s is for good luck, prosperity, happiness, and good health.

For example, traditionally, shrimp symbolizes good fortune, bringing wealth, joy, good health, even laughter, and success to all those who partake in it. Rice, a staple at all Japanese meals, represents fertility and good luck. To top off the heavy o-sechi ryori meal, many families will eat “mochi” (a sweet glutinous rice cake) that is pounded into a dough (photo above) and sometimes filled with bean paste.

With over 100,000 Shinto shrines all around Japan, it is quite easy to find a shrine to pray at during the New Year’s holiday. I have a favorite neighborhood shrine I like to visit at midnight on New Year’s Eve (photo above) where many of my neighbors gather to pray and to drink a cup of sake together. I have become a regular and it is nice to meet and greet neighborhood friends to wish them a “Happy New Year,” which is “akemashite omedetou gozaimassu”, in case you were wondering.

Many people will purchase good luck amulets (photo above) during their hatsumode visit to shrines and temples during the new year. These are called “omamori” and these charms are purchased for good luck and they have different types of significance.

For example, a shrine may be well-known for safe driving amulets, so people will purchase one to protect them from traffic accidents. Most shrines offer amulets for students who may be taking entrance exams. Relatives will purchase these as a gift to the student to wish them success in passing their exams.

Also, people will purchase fortunes for the new year. After reading these, people will tie them on to a tree or a stringed area for good luck (photo above). Again, many students hoping to pass entrance exams will purchase these hoping to pass an important entrance exam.

Regardless of how you celebrate the new year, I wish you all the best in 2025!

Thank you for reading and Happy New Year!

Todd Jay Leonard grew up in Shelbyville but has lived and worked in Japan for over 30 years. He is a university professor, teaching courses in history, cross-cultural understanding, and English in the Faculty of Education, for both the undergraduate and graduate programs at the University of Teacher Education Fukuoka (UTEF). If you have a story idea or questions about Japanese culture, he can be contacted at toddjayleonard@yahoo.com.

Shelbyville Councilman Reed to meet with public on Morrison Park future

Shelbyville Councilman Reed to meet with public on Morrison Park future

Local Letter Carriers collecting non-perishable foods on Saturday with Stamp Out Hunger

Local Letter Carriers collecting non-perishable foods on Saturday with Stamp Out Hunger

Contest winner Tony Bradshaw wins first turf race of 2025 at Horseshoe Indianapolis

Contest winner Tony Bradshaw wins first turf race of 2025 at Horseshoe Indianapolis

205 child sex abuse offenders arrested in FBI-led nationwide crackdown, four Southern District of Indiana

205 child sex abuse offenders arrested in FBI-led nationwide crackdown, four Southern District of Indiana

First Financial Bank earns highest rating from Federal Reserve for community investment

First Financial Bank earns highest rating from Federal Reserve for community investment

Board of Works awards demolition bid for Adams Glass building

Board of Works awards demolition bid for Adams Glass building

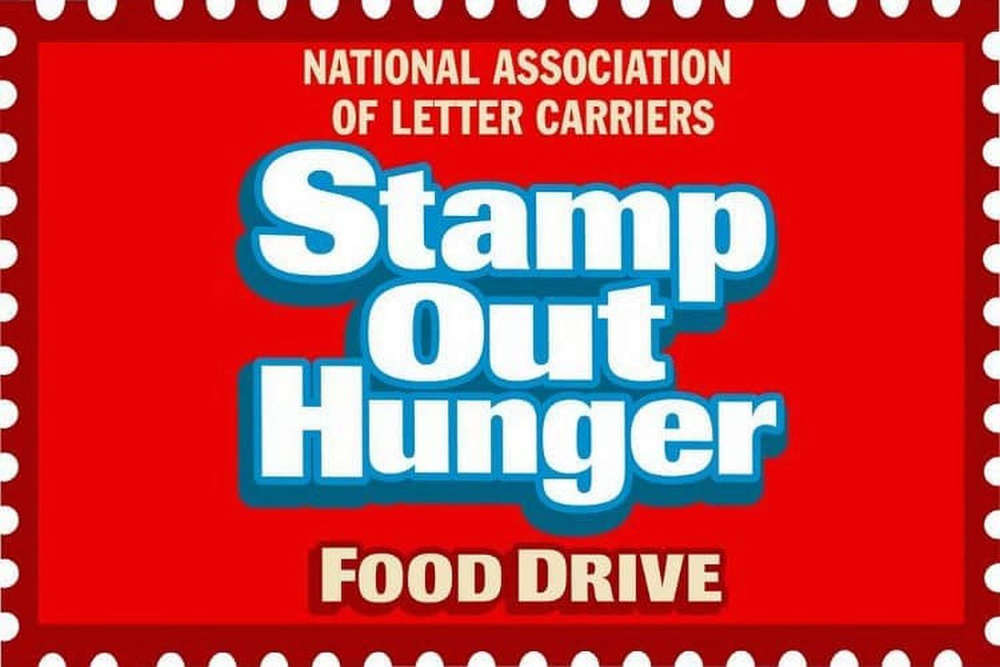

Closure planned on State Road 252 in Edinburgh

Closure planned on State Road 252 in Edinburgh

IHSAA adopts new transfer rules; votes down proposal for co-op teams

IHSAA adopts new transfer rules; votes down proposal for co-op teams