Christmas in Japan, on the surface, seems to be very similar to how Christmas is celebrated in many countries around the world, but when scratching just below the surface, there are some very distinct differences that sets a Japanese-style Christmas celebration apart from other cultures that celebrate Christmas.

A regular reader of this column, Angela, requested that I revisit this topic in an e-mail she sent me. I guess she remembered me writing about it before, but was hazy on the details, and wondered if I could write about Japanese Christmas-related customs again.

Thank you for your e-mail, Angela, and I am happy to do so.

Probably one of the biggest surprises that visitors to Japan have during the Christmas season is how entrenched the custom of ordering KFC chicken on Christmas Eve is here. I mean, it isn’t just a few families that do it, but the large majority of Japanese families all over the country order their chicken dinners in advance (I read where nearly four million families all around Japan order KFC for Christmas Eve every year); each order is then assigned a very strict pick-up time in an assembly line sort of manner that would make Henry Ford proud. (see photo below, buckets lined up for pick-up)

From early November, KFC Japan begins reminding its customers of the upcoming holiday and how they need to get their orders in early. Elaborate displays are set up in the KFC fast food restaurants (see photo, display of merchandise and chicken sets) and since every KFC restaurant here features a life-size statue of Colonel Sanders himself, he is adorned in a Santa suit especially for Christmas — from head to toe — to drive home the point that Christmas is coming! (see photo below, Colonel Sanders as Santa).

So, how did KFC come up with this very lucrative marketing ploy that certainly sees sales spike high on Dec. 24 every year?

The most common legend I have heard over the years is that in the early 1970s, some foreigners were overheard by a sales marketing executive that since they couldn’t get turkey in Japan, they were opting for a KFC bucket of chicken to celebrate Christmas. In 1974, KFC seized upon this idea and began offering chicken dinner sets around Christmas and promoted it in advertising as “Kentucky for Christmas.”

Needless to say, it caught on like a house on fire and the rest is history. Many people cannot imagine a Christmas Eve dinner without a bucket of chicken and its side dishes today. In an unscientific study, I frequently ask my classes how many students ate KFC on Christmas Eve growing up and always, nearly every hand goes up in the air. If it isn’t KFC (for example, they couldn’t get their orders placed in time), then their parents would have some sort of chicken at dinner as a substitute, whether it is homemade or Japanese style fried chicken called “karage” purchased from a local supermarket or restaurant.

The idea of celebrating Christmas by eating chicken is firmly rooted in Japanese Christmas culture and it has become a given and compulsory tradition here. The real winner in all of this is, of course, KFC because — no kidding — they probably do a few months’ worth of sales on that one night each year.

While it is easier to get turkey nowadays than it was back in the 1970s, it is still quite pricy and not that easy to come by without preordering it and arranging for it to be delivered frozen. Also, there is always the issue of having an oven big enough to roast it in, too. Ovens tend to be much smaller so a whole turkey is not that convenient or easy to cook in a Japanese-sized oven.

I have certainly fallen into the KFC marketing trap of thinking I must have KFC on Christmas Eve after living here for 35 years. It is a treat and an easy dinner to have, so every year, I make sure I get my order in early to make sure I have my KFC on Christmas Eve.

In addition to the chicken, KFC offers special Christmas goods each year that people have started collecting. Usually, a plate with the year embossed on it has been a perennial “thank you” gift for a large order of chicken. (see photo below, counter display of chicken sets and goods)

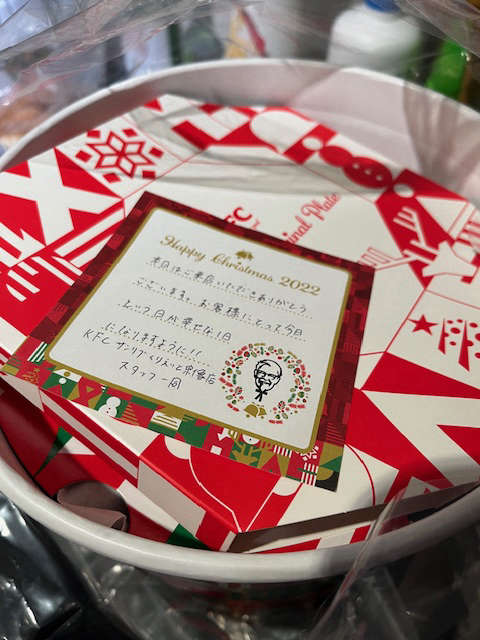

The local KFC near where I live also includes a handwritten note with the order, thanking me for my business and wishing my family a Merry Christmas. Knowing that they have literally hundreds of orders on that day, I always wonder which employee got stuck with the job of handwriting the personal notes for each order. (see photo below, bucket with handwritten note) It is definitely a nice touch, though, and it shows the Japanese attention to detail in service-related industries that Japan is so well-known and famous for all over the world.

In addition to KFC chicken on Christmas Eve, no proper Christmas celebration is complete without “Christmas cake.” (see photo below, the KFC version of a Christmas cake) The history of Christmas cake is much older than the KFC tradition, dating back to the Meiji Period, around 1910.

A well-known cake patisserie at that time, Fujiya, specialized in European-style cakes in Yokohama. It was this shop that first introduced the concept of Christmas cake which is quite different than the typical Christmas cake today. The original one resembled more the Western idea of a Christmas fruit cake and it featured a cake with dried fruits, covered in liquor and a sugary syrup. No doubt, it was likely copied from the British-style Christmas cake tradition of a Christmas pudding that is ladened with brandy and set aflame before it is eaten.

Soon, Fujiya started offering Christmas cake in all of its shops, and when the elite who shopped in the Ginza area of Tokyo started to order them for Christmas is when the Christmas cake tradition in Japan spread throughout the country and today is an important part of the Japanese Christmas tradition.

I have an Australian friend here in Fukuoka who makes a traditional British-style Christmas cake that must be prepared way in advance, starting in November, to make sure the cake is sufficiently cured in an airtight container and turned upside down — this process is called “feeding” the cake. It is very rich and sweet, and the alcohol gives it that extra kick, for sure. I am always honored when I am gifted with part of her handiwork to enjoy during the holidays.

Japanese Christmas cake today in no way resembles the original Christmas cake from 1910. Today, a typical Japanese Christmas cake is more like a “birthday” cake and is nearly always some rendition of a strawberry shortcake (Ichigo Shouto keiki in Japanese). The cake is made up of a very fluffy shortcake that features a layer of cream and strawberries between the two layers, and it is topped off with whole strawberries and an assortment of Christmas-related gewgaws like little Santas, Christmas trees, and other Christmas-related imagery.

Sometimes these are inedible, but often times they are made out of sugar and can be eaten.

A Japanese Christmas cake is actually quite small in circumference. No bigger than a U.S.-sized salad plate — definitely not a dinner plate — and is quite pricey for the size of cake it is. Probably a family of four can each enjoy a nice-sized piece of a typical Christmas cake.

Japanese short-cake is the “go-to” cake for any number of celebrations in Japan, in fact. It is by far one of the most popular types of cakes that is eaten for special occasions such as birthdays, anniversaries, and other celebrations. While sweet, it is not sickeningly sweet like some U.S. commercial cakes are … and the main reason why most Japanese don’t particularly care for American cakes because of the thick, sugary icing.

Another Christmas Eve tradition in Japan is for young dating couples to go out for a fancy meal with champagne and then stay overnight in a hotel to celebrate a romantic Christmas. In the U.S., this type of celebration might be done for New Year’s Eve for young couples in love, but not at Christmas.

Not surprisingly, since Japan is not a Christian country, Christmas Day is an ordinary work day in Japan. In fact, since it is on a Wednesday this year, it is my busiest teaching day. But in just a week, after Christmas, Japanese will enjoy their main yearly family holiday of New Year’s where families gather together to celebrate New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day together.

That will be the topic of my next column in two weeks.

Todd Jay Leonard grew up in Shelbyville, but has lived and worked in Japan for over 30 years. He is a university professor, teaching courses in history, cross-cultural understanding, and English in the Faculty of Education, for both the undergraduate and graduate programs at the University of Teacher Education Fukuoka (UTEF). If you have a story idea or questions about Japanese culture,he can be contacted at toddjayleonard@yahoo.com.

Friday is National Wear Red Day

Friday is National Wear Red Day

Wortman Family Foundation Fund invests in 19 local projects to begin 2026

Wortman Family Foundation Fund invests in 19 local projects to begin 2026

Shelbyville Common Council pushes controversial annexation request to April 6 meeting

Shelbyville Common Council pushes controversial annexation request to April 6 meeting

Ivy Tech Columbus science faculty offering nature hikes

Ivy Tech Columbus science faculty offering nature hikes

Hancock County bridge closed for replacement

Hancock County bridge closed for replacement

Grover Center Museum announces 2026 Exhibition Season

Grover Center Museum announces 2026 Exhibition Season

Ground broken for new headquarters for Indiana DNR Law Enforcement, District 6

Ground broken for new headquarters for Indiana DNR Law Enforcement, District 6

Parker to run for Shelby County Sheriff

Parker to run for Shelby County Sheriff