shelbyville-native-grateful-for-time-with-dodgers-legend-carl-erskine

Mark Risley seized the moment. He picked up the phone and called retired Brooklyn Dodgers star pitcher Carl Erskine.

“I knew he was originally from Anderson and had lived there since his retirement from baseball,” said Risley.

A recent article he had read about Erskine rekindled an interest.

“I had read and heard about Carl for many years and remember a number of people, such as former Shelbyville High School baseball coach Tom Hession, speak well and fondly of him,” continued Risley. “So, I just called him out of the blue and asked if I could come to Anderson to talk about his life and baseball.”

That initial spontaneous phone call in 2017 yielded five visits over the course of the ensuing seven years and a relationship that Risley will forever genuinely treasure.

Unfortunately, there will be no future visits. Erskine died on April 16 at the age of 97.

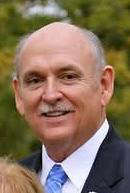

Risley (main photo, right, with Jim Cherry, left, and Carl Erskine, center, at his Anderson home) grew up in Shelbyville and became a lifelong sports and baseball fan. He played in the local Little and Knothole Leagues as a youth and began hosting a sports radio show on WSVL as a high school freshman. He eventually became a full-time employee working in various aspects of the radio business for ten years.

“I was fortunate to have many opportunities through my radio work,” said Risley. “I went to Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium in the 1970s and interviewed several members of the ‘Big Red Machine’ (the Reds teams that won four pennants and two world series). That was quite a thrill. Baseball has always been one of my primary interests.”

Carl Erskine was born in Anderson, Indiana. He broke into major league baseball in 1948 and enjoyed a remarkable 12-year career with the Dodgers. Ten of those seasons were spent in Brooklyn where he was immortalized as one of the “Boys of Summer,” a name author Roger Kahn gave to certain members of the Dodgers teams that played between 1945 and 1955 that were the topic of his book of the same name.

Erskine finished with a career pitching record of 122-78 and a 4.00 earned run average. He won more than 10 games in six of those years including season victory totals of 20, 18, 16 and 14. He set a World Series record for strikeouts in a single game with 14 in 1953 and threw no-hitters in 1952 and 1956.

Erskine pitched two of the seven National League no-hit games in the 1950s. He was selected for the Major League Baseball All-Star game in 1953.

Erskine played on Brooklyn Dodgers teams that won five National League Pennants and the 1955 World Series. He played two seasons after the team moved to Los Angeles and retired in 1959.

Risley was immediately impressed by Erskine’s gracious demeanor.

“He was so welcoming and said I could bring friends,” said Risley. “But he did not just talk about himself. He was intent on talking about the entire experience and the people who shared it with him. He really gave us a sense of what life was like in the 1950s and what it was like to be a major league baseball player then.”

Risley and his friends first met the retired pitcher at the Anderson Bob Evans, however meetings were relocated to the Erskine home following the outbreak of the pandemic.

“Carl and his teammates lived in Brooklyn during the baseball season and he talked about how they would walk to home games at historic Ebbets Field,” said Risley. “It was a special time. The players knew their neighbors and a person could walk through the streets and hear the Dodgers games blaring from house radios.”

The former Dodgers great talked about how wonderful life in New York was during the 1950s.

“He talked about how much he loved going to Broadway musicals,” said Risley. “He remembered seeing ‘South Pacific’ three times. He also told us about being recognized in the audience of the Ed Sullivan Show following his record-setting strikeout performance in the 1953 World Series. Erskine said he received $500 for appearing (that translates to approximately $5,848 in 2024 money).”

The 12-year veteran related that his highest annual salary earned playing baseball was $28,500, which would be about $330,000 in today’s dollars. He came home to Anderson in the offseasons and at one point worked in a lumber yard.

Erskine was throwing in the Dodgers bullpen at the New York Polo Grounds on Oct. 3, 1951, as the Dodgers and the New York Giants battled in the decisive third game of a three-game playoff series for the National League Pennant.

The Giants were at bat in the bottom of the ninth inning trailing 4-2 with two runners on base and one out. Ralph Branca and Erskine were warming up. Before Dodgers manager Chuck Dressen went to remove starting pitcher Don Newcombe, Dressen asked the bullpen coach who would be the better reliever in this situation.

“Carl said that the bullpen coach told Dressen that Erskine was bouncing his curveball and that Branca would be the better choice,” stated Risley.

Branca entered the game and delivered a pitch that became known as the ‘Shot heard round the world,’ as Bobby Thomson hit the home run that won the pennant for the Giants and went down in history as one of sport’s most iconic moments.

“Carl said that bounced curveball turned out to be his 'best pitch’ because it spared him the high stress situation of possibly throwing the pitch that cost the Dodgers the championship,” said Risley.

Erskine developed a strong relationship with Jackie Robinson (photo), the man who broke the major league baseball color barrier in 1947.

“Carl said Jackie was very kind to him during spring training before the young Erskine was called up to the major leagues,” said Risley. “When Carl joined Jackie with the Dodgers the following year, Jackie thanked him for always being so cordial and considerate in reaching out to his family.”

The Dodger legend talked about growing up in Anderson and playing sports with Johnny Wilson, who led Anderson to the 1946 Indiana state basketball championship and was named Mr. Basketball. Wilson was intent on playing at Indiana University but was precluded from doing so by a de-facto “gentlemen’s agreement” among Big Ten coaches not to recruit black players. Carl related Wilson’s story to Risley.

“He commented that he was very happy to be part of Jackie’s achievement after seeing his good friend Johnny Wilson denied a prime, historic opportunity.”

Erskine told Risley he never saw color and credited his youth in Anderson for providing him that enlightened perspective.

Wilson went on to become a superstar athlete at Anderson College where he earned 11 letters and became a two-time basketball All-American. Ironically, two years after Wilson was denied the opportunity to play at IU, Shelbyville’s Bill Garrett, who led Shelbyville to the Indiana state basketball title in 1947, enrolled at Indiana University and became the first black player in the Big Ten.

The Dodgers broke the hearts of the Brooklyn faithful when they moved to Los Angeles in 1958. Erskine took the mound as the starting pitcher in the Dodgers debut game versus the San Francisco Giants at the Los Angeles Coliseum before 79,000 enthusiastic fans on April 18, 1958. He scattered 10 hits and struck out seven over the course of eight innings en route to claiming a 6-5 victory.

Erskine pitched his final game for the Dodgers on June 14, 1960, at the age of 32. He returned to Anderson with his wife, Betty, and their four children. He worked as a color commentator for one season on ABC’s Saturday afternoon Major League Baseball broadcasts with respected play-by-play announcer Jack Buck.

He coached the Anderson College baseball team for 12 seasons. His teams won four conference championships. The 1965 Anderson squad finished 20-5 and made an appearance in the NAIA World Series.

He moved into the banking profession and became president and board vice-chairman of the Star Bank in Anderson. He served on the advisory board of the Baseball Assistance Team which is a non-profit organization that addresses the financial and mental health issues of former Major League, Minor League, and Negro league players.

Erskine’s youngest child, Jimmy (photo), was born with Down syndrome.

“The Erskines were unconditionally devoted to Jimmy and provided him with an exceptional quality of life,” said Risley. “Some medical professionals suggested that he be institutionalized, but Carl and Betty resisted. They brought Jimmy home and provided him with a lifetime of love and attention.”

Jimmy became a favorite in the Anderson community and enjoyed a full and satisfying life until his passing this past November.

“My wife, Michelle, and I attended his funeral and it was packed,” stated Risley.

Erskine became a passionate advocate for Special Olympics. His commitment to this cause was commemorated with the Carl and Betty Erskine Society which promotes and supports Indiana Special Olympics.

The Anderson native received numerous honors throughout his life. The National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum presented him with the Buck O’Neil Lifetime Achievement Award for his community service and dedication to Special Olympics.

A statue of Erskine stands at the site of the Carl D. Erskine Rehabilitation and Sports Medicine Center.

Erskine Elementary School in Anderson was constructed on land donated by Erskine.

Erskine Street in Brooklyn is named in his honor.

He was a three-time recipient of the Indiana Sagamore of the Wabash honor and received the Sachem Award from Governor Mitch Daniels in 2010.

Ted Green’s recent documentary, “The Best We’ve Got: The Carl Erskine Story,” chronicles Erskine’s life and is a fitting tribute.

“Wrapping up one of the breakfasts, Carl told us how it was blessing to him that we wanted to hear his stories from many years ago,” said Risley. “I responded that we were the ones who were blessed.”

Erskine once commented that his faith provided him the strength he needed to work through his life’s most difficult challenges.

“Carl professed a deep commitment to his Christian faith,” said Risley. “He utilized it as a foundation for his life.”

In addition to the five in-person visits, Risley recalled several phone conversations with the Dodgers great.

“I talked with Carl on the phone three or four weeks before he died,” said Risley. “He amazed me with his answers and as always, was in good spirits. I didn’t want to be a nuisance but his wife always encouraged me to keep calling because Carl loved to talk baseball with his fans. I visited him at his home on two occasions last year and planned to travel to Anderson to see him in May.”

Carl Erskine became the last of the Boys of Summer to pass away; some 52 years after Roger Kahn’s acclaimed book was released. Eighty-eight-year-old Hall of Fame pitcher Sandy Koufax stands as the only surviving member of the World Series champion 1955 Brooklyn Dodgers team.

Risley’s relationship with Erskine presented both men an opportunity to reflect on a very special period in American and baseball history and enjoy memories of seminal events from the 1950s. But conversations with Risley reveal that the former Shelbyville resident received an even greater gift: a special insight into an American sports icon who personified the highest values of the human character.

“I wish I had reached out to Carl 20-30 years earlier, but I am glad that I didn’t wait any longer,” said Risley. “I can’t stress enough the goodness, the class and the humility of this great man.”

The Shelby County Post is a digital newspaper producing news, sports, obituaries and more without a pay wall or subscription needed. Get the most recent Shelby County Post headlines delivered to your email by visiting shelbycountypost.com and click on the free daily email signup link at the top of the page.

_x000D_

City interested in purchasing land for second downtown parking garage

City interested in purchasing land for second downtown parking garage

Knauf Insulation to become first fiberglass insulation manufacturer formaldehyde free by end of 2025

Knauf Insulation to become first fiberglass insulation manufacturer formaldehyde free by end of 2025

Site development plans approved for Speedway, Circle K

Site development plans approved for Speedway, Circle K

ISP shopping safety tips

ISP shopping safety tips

Silver Alert declared for missing Indianapolis teen

Silver Alert declared for missing Indianapolis teen

Hope and Rushville awarded OCRA grants

Hope and Rushville awarded OCRA grants

School board approves curriculum additions at Shelbyville High School

School board approves curriculum additions at Shelbyville High School

Shelbyville senior receives 2026 Lilly Endowment Community Scholarship

Shelbyville senior receives 2026 Lilly Endowment Community Scholarship